Have you ever heard of the Prehistoric Rusyns? What can history tell us about them and their past? The answer is quite simple—absolutely nothing! Not because they didn’t exist, but rather, because you can’t have a history before it was written. This is after all the definition of a different term in prehistory.

History, logically, cannot tell us anything about something before it existed!

That statement may sound obvious, but the issue is unless it’s actually defined, do modern people really understand what history as an academic discipline is; do people care to learn this discipline, how to not simply read, but study history? It’s not the same thing, anyone literate can read a story, but can they critically examine it?

Now more than ever it’s easy to read whatever we like, there is ab abundance of material on every subject online, but a little bit of learning, or knowledge without wisdom, reading a few articles but not understanding the bigger picture can lead to serious misunderstandings. History is the story of humanity, and something so grand and complex requires study, we can’t simply read it like we would a novel, and to study history, we must understand what it actually is.

Though there has long been an issue with history among Rusyns, the same issue exists among other East Slavs. To paraphrase medievalist Dmitry Likhachov, few other people’s histories are cloaked in so many contradictory myths and versions, a few other folks interpret their own history or nationality as variously as do these people.1

As matter of fact, this issue with history can be applied to much of Eastern and Central Europe, and many of the civilizations therein, and really, any lands at the crossroads of different civilizations. Where there are different religious, national, and cultural worldviews existing on the same territories or states, it follows that numerous and often radically different interpretations of history or schools of histography will emerge.

This was the case in the Carpathian region, when in the same century, and among the same peoples, living even in the same cities, there developed entirely different national ideas. For example, the Old Ruthenian, Russophile, and Ukrainophile identities, which all developed side by side, and in some ways concern a people so similar, yet who also paradoxically, can be so far apart.

This all concerns the issue of interpreting history, which we discussed in a previous publication. But what about the study of it? Thanks to the internet, it’s now possible for everyone to have access to information at a level unprecedented. Whereas 50 years ago, one had to consult physical records, and much information regarding East Slavic cultural heritage was not accessible for people, especially in the west, to read about, young Rusyns can now find out about their heritage like never before. This gift has become a double-edged sword, however, as just as the internet allows information to be disseminated at an unprecedented level, it also allows myths, the phenomena of “fake news”, and simple falsehoods malicious or not, to be spread.

In the times of our parents and grandparents, to learn about the history of a certain Slavic tribe, one would at least have to consult published materials in a library or take studies in a university, now one can find any bit of information they want, written by whomever online, the well-researched scientific history, the myths, and simply misinformation side by side.

So now, while we suffer slightly less from the issue of the unavailability of information, we often suffer more from unreliability. There’s the old saying I once heard from Fr. Thomas Hopko “paper suffers anything”, well now it’s even worse, because of the internet, you can spread any insufferable theory around without even needing paper!

There is nothing more dangerous than someone who knows just enough about a subject to get it horribly wrong, the phenomenon of reading a Wikipedia article or two, (which can be a great starting place [!] ) but then considering oneself an expert on a subject without taking that study farther—essentially, the phenomenon of being a “self-proclaimed internet expert”, with no serious study.

This is not to say one cannot become an expert through personal studies, as opposed to formal classes, in many cases, the best education comes through individual research. But that research should be conducted with serious discipline if one wishes to avoid the various pitfalls of misinformation out there.

It’s not enough to simply read history materials, one should also learn how to study history as a discipline in itself.

For young Rusyns, an appreciation for history is even more important, as it’s so much more difficult to gain a comprehensive education in their history, due to not only the issues with interpretation, which exacerbate the situation, but the simple fact that most modern people don’t seem to appreciate history very much, and so they don’t want to learn the essence of what history actually is, and the theory of how to study it.

A very good mental exercise, just to demonstrate the importance of this classical and comprehensive study, is to return to our question.

What can history tell us about prehistoric Rusyns?

We already answered the question — nothing. But why is that?

The issue here is not only the particular problem of history among Rusyns and East Slavs, it is also the fact that some people do not understand what history actually is.

This author believes the principles of classical education can help us. We must not approach historical studies by looking for facts we agree, with but rather looking for objective truth and honestly expressing or subjective opinions. We must learn how to objectively study history, how to critically examine historical sources, and how to distinguish history from myth.

History and myth are not necessarily even opposites—they both play an important role in the human story. If we understand their role, we will not only learn history better, but learn how to better interpret it, by understanding what history actually is, and how it develops, which is of paramount import for Rusyn as a tragically underrepresented people. Before we can enlighten the world about Rusyns, we have to know where we, as humans, come from, and how we got here—our tale from bygone years.

What is History?

History is commonly (mis)understood as being simply “the past”, or “things which happened a long time ago.” Some may elevate this definition a little and say, “history is the study of events which happened in the past”, and of course, this is basically true, but there is a key criterion which determines whether or not this study is history—that is, how are these events studied; by what means or medium are these past events studied?

For example, we don’t really call the study of how volcanos and fossils are formed “history”, even though it happened in the past, rather, it is geology or paleontology. We were not there to witness those events, no humans have observed and recorded these events as they happened. These events are studied by an entirely different scientific process from historical studies. So, what is History then?

To answer this question, perhaps we should first ask, what is Prehistory?

Prehistory is the time before recorded history. With this understanding, we may begin to see what history—as an academic discipline—actually is. This becomes even more clear when we know that another term for prehistory is pre-literary history.

The fact is—history—as an academic discipline—in its purest sense is a study of literature!

History is the study of the past primarily through recorded sources, through narrative, and it is precisely the study of these tangible and extant sources, which makes a study history in the strictest sense.

Seeing as the primary way these sources are recorded is through writing, history is primarily the study of written historical sources.

Once written sources exist, and are available for us to study, this becomes history. And before there are any recorded sources, we are dealing with pre-history. History may indeed be considered a school of literature, but not just any literature, strictly speaking, qualifies.

One of the criteria which distinguishes written history is that it attempts, ideally, from a neutral point of view, to record events that occurred by having witnessed them, or speaking to witnesses and recording their accounts (making the work of history a primary source), and by collecting and analyzing evidence.

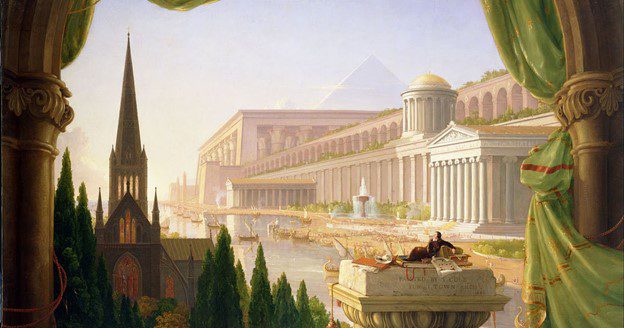

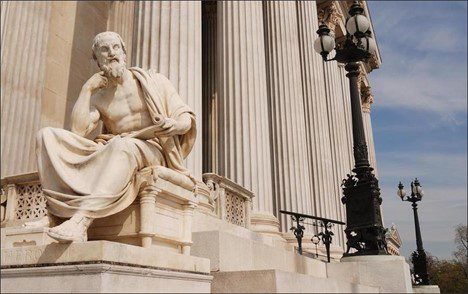

We generally consider the ancient Greek writer Herodotus (484-425 B.C.) to be the “Father of History”, for his monumental and keystone work The Histories, in which he compiled what we consider the first systematic study of history in the known world. “Histories”, in this Greek context, would be more properly translated as “Inquires”, and “History” (ἱστορία – Historía) thus means “Inquiry”, i.e. knowledge gained by asking questions and systematically researching the events in question.2,3

As a result, Historical Studies or history as an academic-literary discipline, can be understood as making inquiries into the past, primarily by the use of sources—either interviewing people or seeking our records, or any combination.

Herodotus extensively traveled the Hellenic oikumene, and made inquiries into events, recording what he observed, and what he was told by witnesses.4

It is for this reason that we traditionally call Herodotus by this name. This title helps us to understand what history really is. He could not be the father of history if history was simply “events which happened in the past”, obviously Herodotus is not the source of all events which happened prior to his birth! He is not even close to being the first human writer, or the first human to record past events.

Herodotus is called the “Father of History” because he was arguably the first person to record history with an approach similar to the modern academic discipline, i.e. by focusing on systematically recording primary sources, personally traveling and witnessing events, and speaking to witnesses, and if and when these witnesses disagree or contradict, he would often describe both positions, and leave the matter to the reader to decide. The systematic aspect is the key in determining what constitutes what is or isn’t.

Herodotus has not only been universally praised as the “father of history”, he has also been slandered by some “the father of lies.” This is also important to our understanding of history as a school of literature. We may understand this to mean not that Herodotus is either a historian or a liar, but rather, that history itself may contain lies, for example, one of the sources he interviewed could have lied to him, or simply been mistaken.

But History is not always fact, it is not an account of facts that happened in the past, it is simply a story of the past—the reliability of the story may vary greatly. We all know the adage “History is written by the victor.” Others would add that history is “his story”, and while I don’t question the overrepresentation of male perspectives in history, I would only point out as a Hellenist, that the “H” in history is silent, (it merely represents an archaic breath mark), there is no “H” in the original word (ἱστορία), therefore we could say history is neither his or her story—history – is story—that’s all it is—narrative. And narrative is dependent on the narrator.

It is crucial to understand that while reputable historians try to mitigate it, a certain degree of bias is inherent in history. History is not purely events which have happened in the past, it is the man-made records of these events—not the events themselves.

The presence of bias is not inherently malicious, as all historians naturally approach past events, and interpret them from different angles, positions, and opinions. As a matter of fact, even if a source is incredibly biased, to the point where it’s considered unreliable for relaying facts that occurred, this does not in fact mean this source is not history. It would not be a reliable source to cite as proof of a fact but provided it is significant, it can and should be studied as an example of a history of the subject, the fact that it’s incredibly biased would be a noteworthy and important detail.

As a matter of fact, some would argue it isn’t even possible to be one hundred percent unbiased, and thus, it is better to simply acknowledge transparently where your biases are and try to mitigate them as much as possible.

It is a key aspect of history, that historians of different nations and ideologies examine and interpret the same events in different ways, and come to different conclusions.

When different historians from certain nations or schools of thought systematically interpret, categorize, and tell history in this coordinated way, we may call it a school of history or rather Історіоґрафія.

We may say history writing is a presentation of the sources whereas histography is an interpretation.

For example, if Russians consistently translate the word Rusin as “Russian”, and consider Vladimir-Suzdal the successor of Kievan Rus’, and Ukrainian historians, looking at these same things, say that Rusin is an archaic word for Ukrainian, and that the Kingdom of Galicia was the legitimate successor of Kievan Rus’, we may call these the Russian or Ukrainian schools of histography. This is the way these people understand their history, and that of their neighbors, it is biased, but not necessarily incorrect, as it is often opinion-based. How do we objectively determine who is the “true Rus’?” We cannot, we may only present the facts, evidence, and arguments. It is only when these opinions of histographical schools are passed off as hard facts, that it becomes problematic.

For example, if certain Ukrainians say that citizens of Kievan Rus’ called that state Ukraine, or called themselves Ukrainians,[5][6] (most educated Ukrainians do not do this, however it is common among revisionists and ultra-nationalists), or if some Russians say all Ruthenians always7 desired unity with Moscow and considered themselves enemies of Poland-Lithuania,8 this is historical revisionism, as it is modern people, or pseudo-historians often anachronistically inserting their own interpretation of events, which do not exist in or are otherwise not supported in any of the sources. Essentially, it’s rewriting history, usually to support a certain modern agenda—i.e. revisionism.

However, while any reputable historian strives to write honestly, something does not have to be true, to make it a historical source or record, it merely has to have been recorded by humans in the past.

History is a school or study of literature, therefore literary criticism, comparing and contrasting different sources to each other and to the existing well of knowledge is a key part of historical studies.

In her seminal work, The Well-Educated Mind; a Guide to the Classical Education You Never Had, which demonstrates how a foundation in classical education can teach us how to truly learn from the wealth of human literature, and the importance and art of not simply reading, but studying books, Susan Wise Bauer gives the following recommendations for reading history — which, again—is a school of literature:

As you read history, you’ll ask yourself the classic detective (and journalist) questions: Who? What? When? Where? Why? At the first level of inquiry, ask these questions about the story the writer tells: Who is this history about? What happened to them? When does it take place, and where? Why are the characters of this history able to rise above their challenges? Or why do they fail? On the second level of inquiry, you’ll scrutinize the historian’s argument: What proof does she offer? How does she defend her assertions? What historical evidence does she use? Finally, on your third level of inquiry, ask: What does this historian tell us about human existence? How does history explain who men and women are, and what place they are to take in the world? […]

Once you’ve grasped the content of the history, you can move on to evaluate its accuracy. […] Does the story told by the historian make good use of that outside evidence? Or does it distort the evidence in order to shape the story in a particular way?

Once you’ve asked yourself what sort of evidence the historian gives you to connect question and answer, take some time to examine this evidence. You probably won’t be able to pinpoint errors of fact; this would require you to look at the actual sources the historian uses. But you can evaluate how the historian is using the evidence he cites. Using rules of argument, you can decide whether or not the historian is treating his evidence fairly— or whether he is playing fast and loose with it in order to come to a hoped-for conclusion. As you evaluate the evidence, look for the following common errors:

- Misdirection by multiple proposition.

- Substituting a question for a statement.

- Drawing a false analogy.

- Argument by example.

- Incorrect sampling:

- Hasty generalizations.

- Failure to define terms.

- Backward reasoning.

- Post hoc, ergo propter hoc: Looking for causation is always tricky, and historians are particularly prone to the post hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy—literally “after that, therefore because of it.” This is the fallacy of thinking that because one event comes after another in time, the first event caused the second event.

- Identification of a single cause-effect relationship.

- Failure to highlight both similarities and differences.

[…] Academic qualifications aren’t necessarily the mark of a good historian. But historians who have been trained within the university are more likely to identify themselves with a particular school of historiography than nonacademic historians (such as Cornelius Ryan). Understanding a historian’s training and background can help you understand more clearly how a historian’s work might fit into the categories above. […]

Once you’ve understood the historian’s methods, you can reflect on the wider implications of her conclusions. What does the historian say, then, about the nature of humans and their ability to act with purpose—to change their lives or control the world around them?9

Of all the fallacies Bauer mentions, “hasty generalizations”10 is one of the most common issues in East Slavic histographies. For example, let’s consider:

Russians/Ukrainians/Rusyns have always identified as/with [insert nationality or ideology].

While we can not explore here all the over-generalizations, nor can we say all generalizations in every context are inherently bad, (we can even say this may be acceptable in opinionated or rhetorical writings), within the discipline of historical writing, it is best to stick with specifics: i.e. between [these time periods], the majority of the writers in [these areas] identified [with these groups], and provide examples and/or sources. What must be avoided at all costs is revisionism and confirmation bias, it is important to represent historical sources as they were, not as we think they were or rather would like them to have been.

What must be remembered is that history is the study of past events by primarily studying literary sources. If there is no study of written historical sources, then this is not history but another science is being conducted, anthropology, sociology, or paleontology.

A Prehistory for each nation?

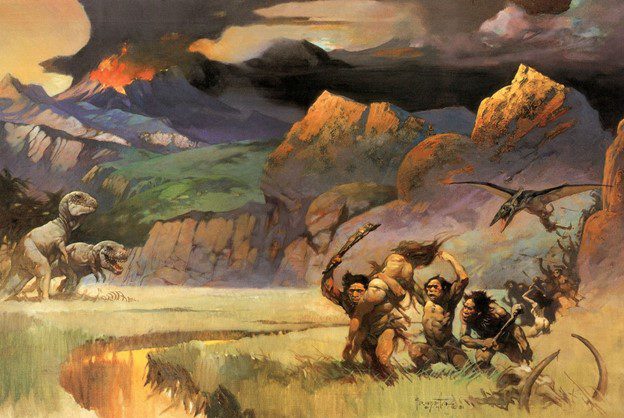

There is another misconception that Prehistory was one single period in human history that we all collectively entered or existed at the same time. In other words, Prehistory as it’s understood is some vague “stone age”, the days of cavemen or dinosaurs. While -that is indeed prehistoric, Prehistory is not one specific period of time.

As we discussed, history is the study of sources, and prehistory is pre-literary history—the period before written or recorded history appears or is extant for us to examine. Therefore, every people have different prehistoric periods.

For example, Greek written works already exist in the bronze age, however we cannot speak of the bronze age history of Britain, Scandinavia, or the 5th-century history of the Slavs.

This does not mean no cultures existed in these lands and we can’t study these periods.

It simply means there are really no written sources from these lands or peoples describing events of these times, so with no history available to us from these times, we may say they were in their prehistoric period.

Saeculum Obscurum

The term “Dark Ages” is another example of a concept which people misunderstand in history, and due to its subjective and potentially misleading context, and modern historians by in large reject this term. The context of the word “Dark” naturally colors this vibrant and dynamic period in people’s minds with a negative overshadow. Dark implies here an ominous or even malevolent age, a time of troubles, an uncivilized age of barbarism and ignorance. The image most people tend to have when they hear the word “Dark Ages” is not unlike the verse of the Norse Edda:

An axe age, a sword age, shields shall be cloven, a wind age, a wolf age, ere the world sinks.

That apocalyptic description comes from dark age mythology and did not reflect the reality of the time, however, it does, unfortunately, reflect the pop culture understanding of this time.

So many myths surround this period, that it was a horrible, dark grey time—we see this particularly reflected in movies and artistic depictions, when peasants and even noble knights are depicted in colorless clothing, covered in dirt, when in fact, medieval fashion was quite vibrant.

While it is true that the term “Dark Ages” was also used by historical people with a perjurious context, lovers of the Renaissance juxtapose the dark ages as a time of ignorance or degradation compared to classical antiquity, with its relative advancements.11

18th century free thinkers considered the dark age to be ignorant and regressive compared to their advanced and “enlightened” “age of reason”.12

This whole conceptualization of the dark ages, however, is not an objective historical description of the past, it is a histographical interpretation. That is to say, the dark ages are not a concrete time and reality, the term reflects the way different thinkers viewed or interpreted them. Professor Ralph Raico points out:

“The stereotype of the Middle Ages as “the Dark Ages” fostered by Renaissance humanists and Enlightenment philosophes has, of course, long since been abandoned by scholars.”13

Modern historians by in large reject this prejudiced label as not only misleading but simply untrue.14 In An Age of Tyrants: Britain and the Britons, Christopher Synder writes:

“Historians and archaeologists have never liked the label Dark Ages. For even though written records from this period are scarce and archaeological finds are difficult to date and interpret, there are numerous indicators that these centuries were neither “dark” nor “barbarous” in comparison with other eras.”15

In any case, the Dark Ages were understood by both historical and modern people with the negative connotation the name implies, but that is not necessarily accurate, or the way modern academic historians use the name.

Today, we call these ages “dark” primarily due to the relative lack of sources, records, and information we have surviving from this period, compared to the relative abundance from classical antiquity. In other words, they are “dark” because we don’t have as many records to “shed light” on them, and thus we are more “in the dark” on these times.

The analogous Latin term Saeculum Obscurum can help us to better understand the Dark Ages — obscure age.16

Much like the difference between history and prehistory is the presence or lack of sources, historians use the term dark ages to refer to this period when there are comparatively fewer records.

For example, we have detailed records of the Peloponnesian War, but very little concerning the Greek Dark Ages centuries before. We have many records from the time of Emperor Justinian in Constantinople but comparatively less from the Byzantine Dark Ages, it could even be argued we know more about the Roman Conquest of Dacia than later the Hungarian conquest of Pannonia.

So, while Prehistory and History are more absolute or dualistic categorical terms, for the time before and after records appear, “Dark Ages” is a relativistic term that can be applied to periods when sources or records are more scarce than in other periods by comparison, or likewise when the people of that period have seemingly lost records or knowledge from previous ages.

Modernism has led people to believe that progress goes on continuously in a linear advancement, but history shows us it ebbs and flows, we advance and we regress, sometimes we have golden ages and sometimes we slip back into dark ages where records or advancements are lost.

It is best for objective historical studies that we use the term dark ages in the context of a Saeculum Obscurum, an obscure period with a lack of records, and nor perjuriously to simply mean a “bad” time, as this is a subjective interpretation which moves away from the actual and more practical meaning of a dark age — the scarcity of sources leaving us in the dark on the matter.17

If the term “dark ages” must be used, it’s best that it’s understood in that sense—as an obscure age due to the lack of records—though the term is now avoided due to the negative perception surrounding it, increasing scholarship and availability of sources is calling into question if even the concept itself is true.18

In the end, it always seems most accurate to simply refer to exact dates and specific examples, i.e. the “early middle ages”, the “Synodal Period”, etc. rather than loaded terms such as the “dark ages.”

Archeology has also helped to shed light on where our knowledge had previously been left in the dark due to a lack of sources.

This all serves to show us how very dependent and connected historical studies are to the sources and records. Without them, historians can do very little, without them, we’re in the dark.

It is always possible to shed light on the darkness, there are of course still ways historians can work (especially interdisciplinary with archeologists) to learn more about these times and make them less obscure. Returning to the concept of Prehistory, even in this most extreme situation, when we aren’t dealing with a scarcity of sources but simply lack of sources altogether, knowledge can still find a way.

It should be noted that as new sources from this period become available and have seen the light of day, even the idea of the dark ages as being obscure or lacking in sources is being refuted.

Just because no history exists, however, that doesn’t mean there’s no way for us to learn about these lands or peoples. Having no history certainly doesn’t mean no people existed! On the contrary, in the Romanian Carpathians, there is the famous Peștera cu Oase, or the Cave with the Bones, which contain human remains thought to be possibly the oldest found in Europe, between 37,000 and 42,000 years old! That’s thousands of years before the bronze age, and we know about this!

The interdisciplinary cooperation between historical studies and archeology helps us to form a better understanding of the past.

Archeology vs History

Another common (mis)understanding is that archeology is a school of history, when these fields are related to each other in a similar way as psychology and psychiatry. There is massive overlap but at its core a different methodology. Archeology may generally be understood to be either a school in its own right or otherwise a discipline of anthropology or cultural anthropology.

Archeologists primarily conduct their study by excavating artifacts and trying to understand the purpose they served or the study of human material remains, often categorized into “cultures”, for example, the Urnfield culture or the Cherniakhiv culture.19

Archeology is the primary and most prospective way we can study the pre-historic past, and for this, it has many perspectives and capabilities where “pure history” does not:

Archaeologists can reach back for clues to human behavior far beyond the maximal 5,000 years to which historians are confined by their reliance on written records. Calling this time period “prehistoric” does not mean that these societies were less interested in their history or that they did not have ways of recording and transmitting history. It simply means that written records do not exist.

That said, archaeologists are not limited to the study of societies without written records; they may study those for which historic documents are available to supplement the material remains. Historical archaeology, the archaeological study of places for which written records exist, often provides data that differ considerably from the historical record. In most literate societies, written records are associated with governing elites rather than with farmers, fishers, laborers, or slaves, and therefore they include the biases of the ruling classes. In fact, according to James Deetz, a pioneer in historical archaeology of the Americas, in many historical contexts, “material culture may be the most objective source of information we have” (Deetz, 1977, p. 160).20

Anthropology and archeology emphasize a holistic perspective, which attempts to study human culture and biology “in the broadest possible context” in order to understand their interconnections and interdependence.21

As a result, there are great overlaps between these sciences, and ideally, all these studies and disciplines come together to give us the best picture of the past.

Seeing as Rusyns and Slavs in general, are a people whose literary history begins relatively late compared to the Greeks and Mediterranean cultures, anthropology and archeology along with DNA testing are particularly promising fields for Rusyn and Slavic studies.

However, it is also important to understand the limitations of archeology.

Clearly it has ritualistic purpose…

There’s a humorous anecdote which has become a bit of a meme or running joke, that says when archeologists discover some artifact, or a part of an artifact, and can’t determine what it actually does, they’ll say it “likely had” a “ritual” or “ceremonial” purpose.

As noted, this has become a running joke, as archeologists are obviously aware of this pitfall and try to avoid it just as historians try to avoid bias in writing, but still, we can learn from this.

When dealing with material artifacts which have no mention in sources, we must be careful to simply assume their function.

To be clear, we often can more or less accurately do just that, reconstructive archeology is possible to an extent, however, we must be aware of its limitations.

We may, for example, if we discover a hammer, reasonably assume it was used as a hammer.

But we cannot for example say for certainty if we discover an axe head in the Carpathian Mountains, whether it was inserted from the top and wedged in, or inserted from the bottom, if no materials remain to demonstrate this, and if we have no sources as to how they were constructed.

We cannot simply find a single stone with some illegible carvings on it, and assume this alone is concrete evidence of an undiscovered ancient writing system.

Even if some things may seem very obvious, one should be aware that without a historical source from the period, we cannot assume that ancient people came to the same conclusion as we do about something, or discern their motives and opinions simply from remains.

Archeology can provide us with remains and data about them, but it’s history which provides the narrative.

Archeologists deal primarily in hard facts and empirical evidence, however these things, for example—a bunch of dry bones—can not speak and tell their own story. We may be able to study and gather information from them, however at the end of the day, they cannot tell us a narrative.

History on the other hand can tell us a narrative, however that narrative is not always guaranteed to be true or fact.

Ideally, it’s the synthesis of these studies and bringing all this information together which can really help us to form a more perfect picture of the past.

So, while archeology for example can excavate old bones from the Carpathians, and we can even perform DNA tests on them, we cannot speak to them, and know if they identified as Rusyns, Vlachs, Dacians, etc. We can assume certain things, from the time they date to, but we should not presume to speak for them, and apply nationalist histographies here, and attempt to “claim them” for a particular modern nation when we don’t have written sources from them, and can’t speak to them to hear their own story.

But as established, whereas with written sources, we can hear the accounts of the contemporary people who wrote them, there is only so much we can learn from material remains such as artifacts and bones.

It is not within the power of man to cry out to dry bones and command them to arise, and be renewed, and tell us their story, as only God has done in the vision of the Prophet Ezekiel, and fulfilled this in the resurrection. We can only learn from bones where we came from, and where we all inevitably will go, but neither the bones of king nor beggars have the power to tell us their story. For that, we need history, but even written memory is not eternal, stories fade and are lost, histories are revised, corrected or falsified. For our memory to be eternal, it requires something supersubstantial, something greater. We can only hope that our stories and histories become worthy of eternal memory.

When does Rusyn history begin?

The beginning of Rusyn history is a very important subject which we discussed in a previous study, please consider reading it for more information on this subject, as here I do not wish to repeat what we discussed but to build off of it.

We came to the conclusion that Carpatho-Rusyn literacy history can be said to have begun in the early 19th century, primarily with the publication of Historia Carpato-Ruthenorum, Dukhnovych’s Vruchanie, and this author would add the Mermaid of the Dniester, written in Latin, Slavono-Russisn, and Galician Rusyn respectively. A summary of Rusyn literary history would be as follows:

In General Rusian History

- The word Rusyn was used as early as the 10th century, appearing seven times in the Rus’–Byzantine Treaty of 911 (912),22 conducted between Constantinople and Oleg of Rus’, (which is considered one of the oldest Rusian texts), and six times in the treaty conducted by Igor son of Rurik in 944/945.23

- Rusyn later appears in the first Rusian codex of Laws, the Rus’ka Pravda, which was compiled by Yaroslav the Wise of Kiev, in the early eleventh century.24

- Rusyn appears in the Primary Chronicle, the first Rus’ history, originally compiled around 1113, the oldest surviving copy being the Laurentian Codex, dating from 1377.[25][26]

- In 1501, the first plural use of the word Rusyn was recorded.27

All the examples given above concern the history of Rusyns in the context of “inhabitants of Rus’. We generally must look to the 19th century for the beginning of the literary history of Carpatho-Rusyns:

In Carpatho-Rusyn History

- In 1799 and 1804 respectively, Hegumen Joannicio Basilovits (1742-1821+), who may be regarded as the first modern extant Carpatho-Rusyn historian, published a two-volume work on Ruthenian prince Teodoras (Fyodor/Fedir) Koriatovych, written in Latin, entitled “Brevis notitia fundationis Theodori Koriathovits, olim ducis de Munkacs.”

- In 1837, the Rusalka Dnistrovaya (Русалка днѣстровая) or “The Mermaid of the Dniester” was published in Budapest by Markiyan Shashkevych, and Yakub Holovatsky, and Ivan Vahylevych, who together formed the Ruthenian Troika. This is considered the first work in vernacular (Galician) Rusyn, dedicated to the Rusin nation (In the text: Нарід Руский – Narid Ruski)

- In 1843, Rusyn priest Michaelem Lutskay published in Košice his monumental work Historia Carpato-Ruthenorum for which he may perhaps more accurately be considered the first Carpatho-Rusyn historian, as his work focuses exactly on Carpatho-Ruthenians.

- In 1851, priest Alexander Dukhnovych published his Pozravlenia to the Rusyns, and in this almanac, he wrote the poem “Вручанiе”(Vruchanie – Dedication), the famous hymn “I was, am, and will be a Rusyn.” Which is a great symbolic work for the Rusyn awakening.

- In 1862 and 1867, Austrian historian Hermann J. Bidermann, published his two-volume work “Die ungarischen Ruthenen, ihr Wohngebiet, ihr Erwerb, und ihre Geschichte” which is likely the first scientific-ethnographic study of “Hungarian Rusyns”, i.e. the people of Subcarpathia.

As a result, we can conclude that while the word Rusyn first appears in extant documents from the 1300s (referring to events of the 900s), this was used in a “General Russian”, i.e. Rusian sense, which could refer to an inhabitant of Kiev or Novgorod as much as someone from Carpathian Rus’.

While depending on your perspective, this may be considered part of the history of (Carpatho) Rusyns, in any case, this does not refer exclusively to them, nor was this created by them. The same can be said for most references to Ruthenians throughout the centuries.

Historia Carpato-Ruthenorum is perhaps the most significant document for dating the beginning of Rusyn histography in that it’s written by a Carpatho-Rusyn, about specifically “Carpatho-Rusyns”, and thus we can firmly call it the first Carpatho-Rusyn history, however we should note it is written in Latin.

Dukhnovych’s Vruchanie is a symbolic monument, and it connects Rusyns to their homeland throughout the Carpathian Mountains, though the language is not vernacular.

Finally, the Mermaid of the Dniester is very important, as it is written in vernacular (Galician) Rusyn, and regardless of the differences which emerged between Galicians and Rusyns in the 20th century, the writers of Mermaid in the early 19th clearly considered themselves part of the same Rusian nation and movement as their brothers on the other side of the mountain. From their perspective — we remember that in history we study subjective perspectives as much as objective facts — this was a Rusin work, however it was not a history.

Taking this together, we can connect the beginning of Carpatho-Rusyn literary history and national consciousness, like so many other neighboring peoples, to the mid-nineteenth century, we may say it particularly began between the 1830s to the 1850s, as it was during this period they transitioned from in the strictest sense what we consider Pre-literary history, to extant literary history.

Unfortunately for those of us who love Rusyn studies, prior to the 1800s Carpatho-Rusyns find themselves in a Terra incognita and a Saeculum obscurum.

As we noted before, this obviously does not mean they didn’t exist before or did not produce history prior to then, but this is the period to which we can reliably begin to study and examine history written by then in extant documents and sources.

Prior to the 19th century, aside from records referencing the general region and perhaps the monasteries or castles in Transcarpathia (and we should bear in mind the different social classes and ethnic groups which often inhabited cities such as Mukachevo), there is little in the way of extensive documented sources.

As a result, concerning Carpatho-Rusyns, we must look to archeology and anthropology to study that time before these literary monuments emerge.

What does this mean for Rusyns?

I think this means we must be very conscious about where Rusyns transition from pre-literary history to self-recorded history, so that we can understand what methods of study to use when making inquiries into their past.

We need to understand what sources are extant, so that before they appear, we don’t make the mistake of speaking about, or mythologizing pre-historic cultures with modern or anachronistic biases, national, ideological, or otherwise.

It requires us to be honest about what we can consider factual knowledge about past events, and what things belong more to folklore, oral history, or ethnography.

In other words, we should be careful when talking about the history of “ancient” or “medieval” Carpatho-Rusyns, as the fact of the matter is we have little written history from this time.

There is a temptation, often even unintentional, when dealing with minority cultures, particular those we love, to sort of mythologize the past, to take liberties in “claiming” different figures, and at worst case scenario, when histories simply don’t exist, to invent them, leading to revisionism, and this must just be avoided at all costs.

Especially when dealing with a minority, or stateless nation or culture, that we are trying to spread awareness about to the broader world, it’s imperative that we dispel myths and fallacies about them, regardless whether or not the narrative benefits us or makes our people “look better”, as the moment falsehoods are allowed into history, it can discredit the whole. For example, if we allow potential historical fallacies to be spread about Rusyns, even if they benefit Rusyns, (i.e. portray them in a way that makes them look good) if these fallacies are eventually proven to be false, it can give the enemies of Rusyns a pretext to attempt to deny their whole history, and all the facts concerning it.

Confirmation bias should be avoided in all things, especially history, it’s one wrong thing to lie to another, it’s even more foolish to lie to yourself.

This doesn’t mean historical myths shouldn’t be recorded as part of history as they can often turn out to be true—even if they didn’t happen, as myths often have a certain truth to a people. If anything, a myth of origin is one of the defining pillars of a nation. Myth and “poetic history” have always been valuable and foundational to human civilization. It’s a shame that modern people believe myths are necessarily false. Tolkien once spoke on the value of myth for expressing truth. Whether or not events happened is secondary to the role of myth in early human history, when something is believed enough, especially in nation building and ideology, it can become a reality, hence there’s a saying, “It’s all true, even if it didn’t actually happen.”

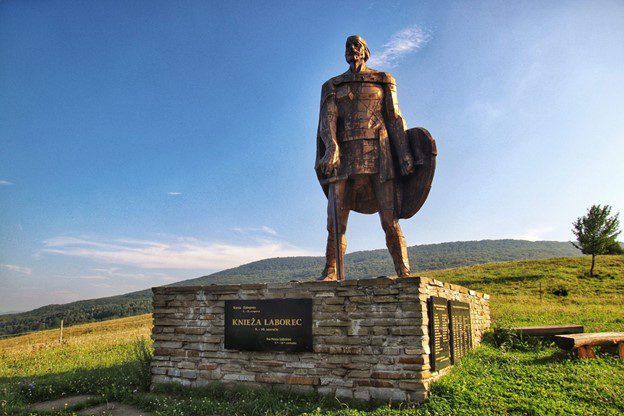

Consider the situation surrounding King Laborec,28 for example. There is nothing wrong with mentioning the Laborec, in Rusyn history or even believing he existed. This author chooses to believe he existed. The issue only emerges if we attempt to pass him off as a figure who absolutely and objectively existed, backed up by concrete records, rather than a semi-legendary figure, for example like Rurik, Askold, or the brothers Lech, Czech, and Rus. Regardless whether legends like Romulus or Rurik were tangible people, they certainly played a crucial role in the foundational history of two great civilizations.

When dealing with figures like Laborec, and the possibility of a medieval Carpatho-Rusyn Principality, all we must do is be honest and state that there is not much documentation preserved from it. We have every right to believe in it, (or not), nobody should be shamed for believing in a traditional myth, we simply need to be able to distinguish between hard facts about the past, those gained by archeology which is a science, and those subjective matters of history which is a school of literature. The history of Rus’ and Rus’ itself, to paraphrase Tyuchev, is not something one can measure with scientific instruments, it’s something one can only believe in—it’s as much a matter of faith as a matter of fact. Faith and Science always could coexist, the only issue is when we misunderstand their respective fields.

The pre-history of Carpathian Rus’ is a field where archeology may help us to learn more.

Another example of historical revisionism we often see along some Ukrainian histographers who insist on using the term “Ancient Ukraine” to refer to Kievan Rus’ or even Scythia in some case, in other words, using the name Ukraine out of context before it appears in history. There is no reason for this; nations may change or develop their names, we no longer call France Gaul, nor do we call Burgundy ancient France.

Regarding the use of the word Ancient with regards to Slavs, we should be aware that while in Slavic, it’s appropriate to use the term drevniy, in English, the word “ancient” in historical writings usually refers Classical Antiquity, which is generally understood to have ended by the 6th century at the latest, and this “ancient” is not a good word to translate drevniy, though it may be used in translation or colloquial speech, however we should not really, in all honesty, especially in English, attempt to describe Slavic nations which emerged after the migration period, as “ancient.”

Another good example of the mythologization of history or poetic history is the whole affair concerning the Hutsuls, who have been turned from a very real tribe into an almost mythical people especially in Ukrainian folklore and histography. Despite the fact that they are very real, there is so much misinformation about them, which is simply repeated to the extent that it’s very hard for most to understand who the Hutsuls actually are.

Hutsuls have essentially been turned into a people about as mythical as Carpathian Hobbits! The same could be said for many of the tribes and the endless arguments over them.

In the diaspora these myths are particularly virulent, legends about the Hajduks or even Carpathian Cossacks as far as Prešov (though cossacks have passed through and near the mountains on the way to the Danube, Carpatho-Rusyns are not Cossacks), the idea of being Russians from the Carpathians (I don’t take issue with Rusyns choosing to identify with Russians, the issue is when they actually seem to believe they are ethnically and linguistically no different than Muscovites which is simply not true) and all the sort of myths that emerged.

What may as well be tales about Carpathian Hobbits, belong more in the realm of Rusyn Fantasy than Rusyn History, and to be thoroughly honest, there’s nothing wrong with that! I would like to read Rusyn fantasy. The development of Rusyn fantasy has just as much value to Rusyn literature as any other genre which is what RLS is all about.

I would only add that this Rusyn fantasy should be judged on whether or not it is good fantasy, and not praised simply for being Rusyn…

The goal is to promote good literature in Rusyn — not to call any literature written in Rusyn good.

Conclusion

Due to the complex history of Rusyns and the lack of awareness concerning them, it’s only natural that fallacies and histories based on legends develops, but this makes it all the more important to correct these historical fallacies starting within whenever they are encountered the Rusyn community itself.

If Rusyns themselves can’t separate fact vs fiction within their own community, they certainly can’t expect other nations to do, and this only plays into the hands of those who would not like the Rusyns to be a nation in the first place.

This requires not only serious academic study and professionalism but also deep honesty and the highest ethical standards. It is very important to avoid confirmation bias, revisionism, and telling the story which is convenient to us, instead of the story which is true. In the end, the truth always comes out and shines light on the darkness, and it must be our conviction that Rusyns stand on the right side of history, in the light.

[1] D. S. Likhachev (1993) Russian Culture in the Modern World, in Russian Social Science Review, 34:1, 70-81.

[2] Joseph, Brian; Janda, Richard, eds. The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Blackwell Publishing, 2003. pg. 163.

[3] Finley, M.I. The Greek Historians; the Essence of Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, and Polybius. The Viking Press, 1959. Pg. 1.

[4] See The Landmark Herodotus by Robert B. Strassler.

[5] Magocsi, Paul Robert. A History of Ukraine; the land and its peoples. 2nd ed. University of Toronto Press, 2010. “Thus, as a term referring to a non-specific and even ethnically non-Ukrainian territory, the name Ukraine dates from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries; as a name for a specific territory, it dates from the late sixteenth century; as a name for lands inhabited by ethnic Ukrainians, it dates from the nineteenth century; and as name referring to a state it dates from the twentieth century.” 189-190.

[6] See also Ibid. 467-470.

[7] Note the sweeping generalizations, “all”, and “always”.

[8] Many among the Orthodox Rus’ nobility, including St. Peter Mohyla, the Ostrogski Princes, Adam Kisiel, while being loyal to Orthodoxy considered themselves also polish patriots, exemplified by the phrase “gente Ruthenus, natione Polonus”, or “of the Rusian kinship and the Polish nation”, Magocsi even describes it as a “Pole of Rus’ religion” (A History…Pg. 157) due to the connection between faith and peoplehood. Many of the western Ruthenian princes did not feel any less “Russian” or Orthodox by their loyalty to the Polish and not Muscovite state, consider how after defeating the Russian Army at the battle of Orsha, Prince Konstantin Ostrogski built a Russian Orthodox Church in Vilnius. For more information on this concept see Ševčenko, Ihor “The many worlds of Peter Mohyla” or Sysyn, F. “Between Poland and the Ukraine: The Dilemma of Adam Kysil, 1600-1653.”

[9] Bauer, Susan Wise. The Well-Educated Mind; a Guide to the Classical Education You Never Had. W.W. Norton & Company. New York / London, 2003. 187-202.

[10] See Ibid. 195.

[11] For example, Hellenistic philosophy, Roman engineering which provides for infrastructural marvels such as roads, domes, aqueducts for running water, the arguably superior Roman model of centralized statehood vs the feudal system. Hence, we see during the renaissance the rise of Romanticism and idealization of the ancient world as a source of inspiration. (It is noteworthy many of these advancements such as philosophy, the building of domes, etc. was never lost in the Byzantine Empire.

[12] Though we would again point out that while Europe was supposedly in a dark age, beneath the titanic dome of Hagia Sophia of Constantinople, they were changing on the patronal feast, on Christmas Day, that Christ had shown the world the “light of reason”, in the Hellenic language far closer to that of Plato and Aristotle than vulgar Latin or the French of Voltaire.

[13] Raico, Ralph. “The European Miracle.” Mises, 2018. Accessed August 28, 2021. https://mises.org/library/european-miracle-0

[14] Tainter, Joseph A. “Post Collapse Societies”. In Companion Encyclopedia of Archaeology. Barker, Graeme (ed.). Abingdon, England: Routledge. pg. 988.

[15] Snyder, Christopher A. An Age of Tyrants: Britain and the Britons A.D. 400–600. Pennsylvania State University Press. University Park, PA, 1998. Pgs. xiii–xiv.

[16] See Nelson, Janet. “The Dark Ages.” In History Workshop Journal, 63. Spring 2007. Pg. 196.

[17] Nelson, Ibid.

[18] Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Migration period.” Encyclopedia Britannica, Accessed August 28, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/event/Dark-Ages.

[19] Magocsi, A History of Ukraine. Pgs. 39-51, especially 44-45.

[20] Haviland, William A.; Prins, Harald E.L.; McBride, Bunny; Walrath, Dana. Cultural Anthropology: The Human Challenge (Fourteenth Edition), Cengage Learning. 2013. Pg. 10.

[21] Ibid. Pg. 3

[22] Суляк, Сергей Георгиевич. Русины в истории: прошлое и настоящее // Русин. 2007. №4. C. 29.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Русская Правда (Краткая редакция) / Подготовка текста, перевод и комментарии М. Б. Свердлова // Библиотека литературы Древней Руси. [Электронное издание] / Институт русской литературы (Пушкинский Дом) РАН. Т. 4: XII век. http://lib.pushkinskijdom.ru/Default.aspx?tabid=4946

[25] Accessible Online: “Laurentian Codex. 1377. Digital reproduction of the landmark manuscripts” was organized by the National Library of Russia, among others. http://expositions.nlr.ru/LaurentianCodex/_Project/page_Description.php?page=1

[26] See also: ПОЛНОЕ СОБРАНИЕ РУССКИХ ЛЕТОПИСЕЙ.Издаваемое Постоянною Историко-Археографической Комиссиею Академии Наук СССР. Томъ первый ЛАВРЕНТЬЕВСКАЯ ЛЕТОПИСЬ. Издание второе Стб. Издательство Академии Наук СССР. 1926-1928. Pg. 155.

[27] Соловьев А. В. Русичи и русовичи // Слово о полку Игореве — памятник XII века / Отв. ред. Д. С. Лихачев; АН СССР. Ин-т рус. лит. (Пушкин. Дом). — М.; Л.: Изд-во АН СССР, 1962. — С. 276—299.

[28] Laborec (Лаборец) was a semi-legendary 9th century Slavic ruler in Carpathian Rus’. As the title Knyaz (Князь) is a cognate of King, and in reality, the context is closer to King than to the most commonly accepted translations Duke and Prince, this author prefers the translation King.